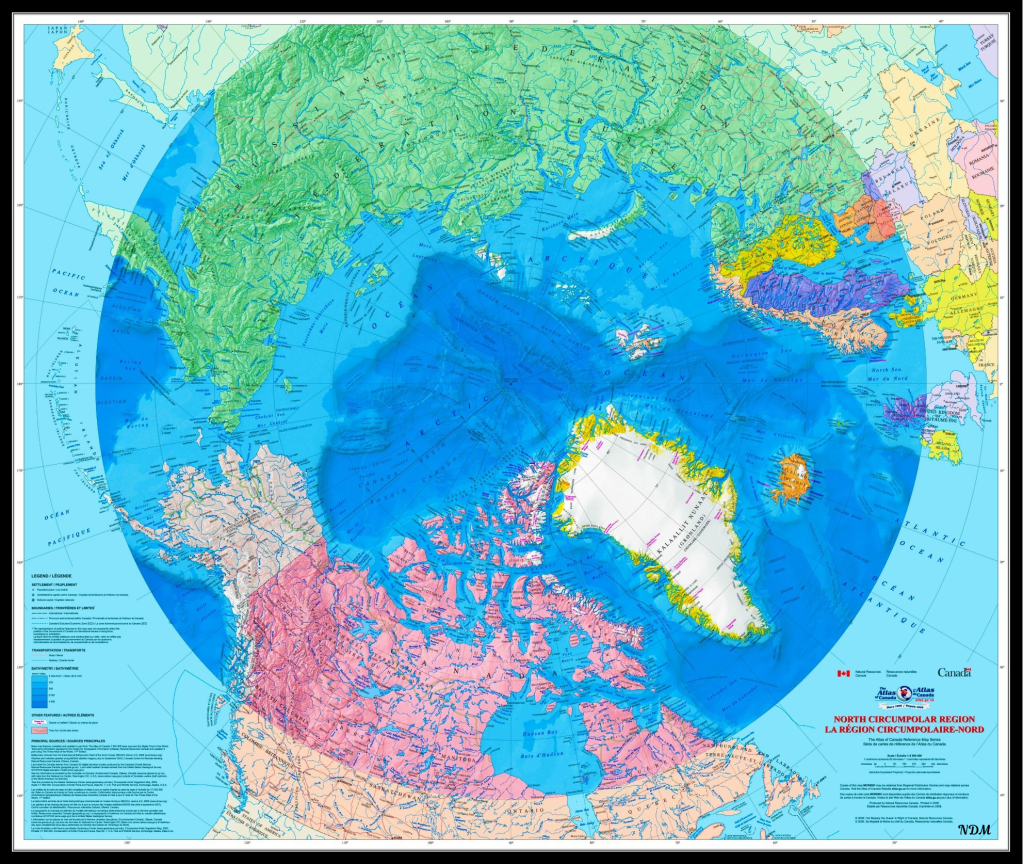

There’s something I say a lot when I’m trying to get people to understand the North and particularly how vast this country actually is. I usually turn it into a question. “If you were to leave Toronto and travel in a straight line north to Alert, Nunavut, how far do you think you’d be going?” People will throw out numbers. They’ll guess. And then I ask the second part. “If you went that exact same distance south, where do you think you’d end up?”

Almost no one ever gets this right. Most people say somewhere in the United States. Maybe the middle of it. Sometimes Mexico.

The actual answer is Bogotá, Colombia. In fact, just a few kilometres south of Bogotá. Every single time I say that, people stop.

Because once you hold that in your head, you can’t pretend the North is abstract anymore. It is a massive part of our country. That distance tells you something about scale, and scale tells you something about vulnerability.

That’s why, when I hear people talk casually about Greenland, I pay attention. With the renewed conversation this week about the United States assigning a new envoy to Greenland, I once again felt very concerned. This isn’t a response to an invitation. It isn’t a request for partnership. It’s the familiar posture of I’m doing this because I want to.

Greenland is not an idea. It is not a strategic blank space. And it is not a prize waiting for a powerful country to notice it. Greenland is primarily Indigenous, specifically Inuit. It is already someone’s home. And for my fellow Canadians it is not very far away. At Canada’s northernmost point, the distance from our coast to Greenland is 26 kilometres, (16 miles) miles. That’s not an ocean separating us. That’s proximity you can almost see across.

Only about 2% of Canadians have ever been north of the 60th parallel, even though nearly half of our landmass lies above it. And even then, most trips north are to places like Whitehorse or Yellowknife, northern cities, yes, but still sub Arctic, still below the tree line.

The Arctic is different. Being above Hudson Bay, above the ice, above the assumptions we carry from the south, that changes how you understand distance, exposure, and survival. It also changes how seriously you take casual talk about “acquiring” places that are already inhabited, already governed, already culturally whole. Those of us who have spent time in the North understand this instinctively.

Remote Indigenous communities are not empty space. They are resilient, deeply rooted, and far too often spoken about as if they exist only in relation to what outsiders want from them. Greenland is no different.

Which brings me to Denmark. I have always had a particular affinity for Denmark, my sister married into a Danish family, and growing up, Denmark was simply part of our world. My brother in laws mother was our Nana Cail. Familiar. Human. Not abstract. So when people talk about Greenland as if it is a loose possession, barely tethered to anything meaningful, it tells me they do not understand the depth of relationships or the weight of history that comes with it. Greenland’s relationship with Denmark is complicated. All colonial histories are. But complexity does not equal vacancy. And it certainly does not create an invitation for others to test boundaries simply because they can. Especially when Denmark is a NATO ally.

At some point, this conversation cannot just come from Denmark or Greenland. It has to come from NATO itself, reminding the United States that when it talks about Greenland, it is talking about a NATO-affiliated territory. This is not a sandbox. These alliances exist precisely to prevent powerful countries from testing limits simply because they feel entitled to do so.

Every time I name Donald Trump in my writings I want to be precise. I am not talking about one man acting alone. I am talking about an administration, a set of enablers, billionaires and a political culture that rewards impulse, spectacle, and domination especially when geography looks exploitable.

As the ice melts and Arctic routes become viable, conversations that once sounded absurd suddenly become operational. The Northwest Passage is no longer something unknown and vague. The United States has never fully accepted Canadian sovereignty over it.

So this is where people misunderstand the danger. Greenland is not asking for partners nor protection. And it is certainly not asking to be spoken about as if it is available.

And Indigenous homelands do not become negotiable because someone powerful has grown bored. If we keep treating places like Greenland as ideas instead of homes, as strategy instead of community, we shouldn’t be surprised when others decide consent is optional.

And history is very clear about what happens when powerful countries confuse proximity with entitlement. If Greenland can be spoken about as available, Canadians would be foolish to think we’re too far away to be next.